Fukushima-related measurements

by the CTBTO

by the CTBTO

Enhanced cooperation with other international organizations

Although the emissions were initially based on estimates only, they proved to be 95% correct as the radionuclides reached the stations mostly within hours of the time predicted. With information made available later by the IAEA on the release level of radioactive substances at the Fukushima power plant – the so-called source term – the CTBTO has been able to quantify and refine its global dispersion predictions.

Click for a regional dispersion simulation (Austrian Meteorological Service ZAMG)

Radioactivity outside of Japan below harmful levels

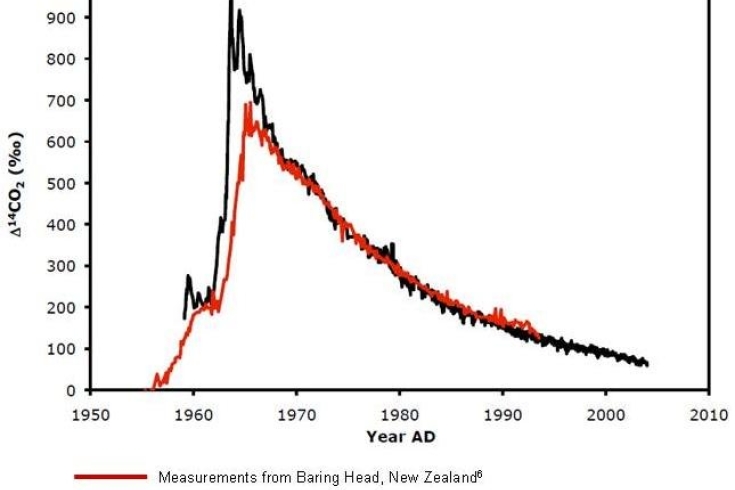

Over 2000 nuclear tests have been conducted all over the world, many of them in the 1950s and 1960s as atmospheric tests.

Radioactive isotopes in baby teeth

By comparison, the levels detected at stations outside Japan up until 13 April 2011 have been far below levels that could cause harm to humans and the environment. The levels are comparable to natural background radiation such as cosmic radiation and radiation from the environment on Earth and lower than from manmade sources such as medical applications or nuclear power plants (under normal operations) or isotope production facilities. This demonstrates how extremely sensitive the CTBTO's monitoring stations are.

Airborne radioactivity due to Cold War nuclear testing. Source: U.S. Department of Commerce, Earth System Research Laboratory.

Monitoring continues

The Philippine Nuclear Research Institute is one of the institutions receiving CTBTO monitoring data.

Background

Nearly 270 monitoring stations, of which 63 are radionuclide sensors, are already operational and send data to the International Data Centre in Vienna, Austria, for processing and analysis. While the system is designed to detect nuclear blasts, it also picks up a vast amount of data that could be used for civil and scientific purposes.

- Update 13 April 2011: radioactivity also measured in the southern hemisphere -

Initial findings

Spreading across the entire globe

Click above for a simulation of the dispersion of radioactivity (German website by the German Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources)

Findings confirm Fukushima release

Click for further information (in German by the German Federal Radiation Protection Agency)

Unparalleled sensitivity

Click to learn how a radionuclide station functions

Benefits for disaster mitigation efforts

Data were also made available to Japan when it was hit by the massive earthquake on 11 March. Tens of thousands of people were tragically killed by the tsunami; still many were saved due to the rapid alerts. According to Japanese authorities, CTBTO data helped them to issue tsunami warnings within a few minutes, thus allowing many people to escape to higher grounds. CTBTO data also helped other countries in the region, such as Australia, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines and the United States, to issue timely tsunami warnings, even though the wave turned out to have lost its devastating power by the time it had reached these countries’ shores.

7 Apr 2011